If your ambition is to write a great movie, don’t go for a happy, sad or – heaven forbid – an ambiguous ending. For a Transcendent Story that touches audiences on both sides of the Hollywood-Indie divide, it’s likely you’ll need “Ecstatic Agony”. Here I explore what that means and why it’s so powerful.

In search of the profoundly moving

In my last post, I identified five qualities that characterise the Transcendent Story and suggested that, of these, the most critical is an ending that is profoundly moving.

Indie films often won’t achieve this, possibly because they’re a bit shaky on story craft or maybe because they fear that if they moved the audience it might ruin their reputation for ironic detachment.

But, the Hollywood film that touches us deep down in our souls is even rarer and that’s a little strange because Hollywood exists to please the broad audience. So why aren’t studio pics moving us? Because I think there are some misconceptions about what audiences are looking for in an ending.

The limitations of the Happy Ending

The conventional wisdom is that commercial audiences are seeking a “happy” ending.

Taken’s success at the box office suggests its restorative ending works at some level but would you say it was a transcendent experience?

If a nice father (like Liam Neeson) has his daughter kidnapped, he should end up saving his child and belting the crap out of the bad guys.

Or, in a battle between a bunch of superheroes and an antagonist from some alternative universe who’s slipped in through a wormhole, the comic book protagonists should prevail – though ideally in a way that suggests a money-spinning sequel.

And, of course, in romantic comedies, the boy simply must get the girl.

Happy endings like these tend to work pretty well at the box office, it’s true, and it’s not hard to see why.

Life is hard and achieving a positive outcome in our own lives – personally or professionally – can be a rare occurrence, so it’s easy to understand the appeal of seeing the person you’re rooting for triumph up there on the screen. Just as it’s nice to see your sporting team get up over that other mob.

You would think that it would be obvious that endings should be happy. But you would be wrong.

The limitations of a happy ending

I would suggest that films with these sorts of endings, where the hero gets what they set out to get, do deliver deliver the Catharsis I talked about in an earlier post. However, will they profoundly move us? Will they make us feel Joseph Campbell’s “rapture of being alive”? No, I would say that generally they will not.

Think about it. How did you feel at the end of Taken? Or The Avengers? Or 27 Dresses? You felt OK, right, but they didn’t take you to a spiritual place, did they?

So if a happy ending won’t profoundly move us, should we shoot for a sad ending? No, that typically won’t cut it either.

The limitations of the sad ending

There are a lot of films with sad endings that have done incredibly well at the box office.

In Australia, the tiny film Red Dog featured – SPOILER ALERT – not just the death of the titular canine but also that of the male lead – and it grossed more than $20m – a huge amount in a country less than one-tenth the size of the USA.

Love Story and Beaches are just a couple of examples in the subgenre of Cancer Weepies that have been incredibly popular with audiences.

In Titanic, the highest grossing film in history until it was pipped by Avatar, not only does the liner sink with the loss of more than a thousand lives, but the romantic lead is one of those who heads to Davy Jones’s Locker.

Some can’t watch these films without ready access to a box of Kleenex but I sit dry-eyed. Why? Because plain “sad” just doesn’t do it for me. I’m sorry to keep harping on about it but these films just do not make me feel the rapture being alive.

Why happy and sad endings fall short of greatness

Why do happy and sad endings seem to work for some audiences but still seem to fall short of being profoundly moving?

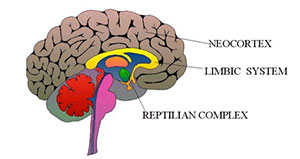

Some films appeal to the lower order reptilian and limbic (mammalian) parts of the brain – but the great films tend to also exercise the more evolved and higher order neocortex.

I think it’s because the sort of “victory” you get in Taken or The Avengers is only satisfying to the primal reptilian part of our brains – the bit that used to gain pleasure from evading a ravenous sabre-toothed cat.

And it could be because the sort of happy ending you get in a formulaic romantic comedy like Pretty Woman or the sad ending you get in a tear-jerker like say The Notebook is only operating on the slightly more evolved touchy-feely mammalian (limbic) part of our brains.

I’m not knocking these sorts of films. There’s clearly an audience for them. But I think that for a film to be profoundly moving, it needs to exercise our entire brains – not just the lower order reptilian and mammalian elements but also the more sophisticated and most recently evolved neocortex. It needs to grapple with the eternal, metaphysical issues that I identified in my last post, and I think the emotions evoked by the ending need to draw from a wider range of the emotional palette – because life is neither happy nor sad. The frustration and the wonder of life is that it’s both.

Which leads me to the idea of Ecstatic Agony.

Ecstatic agony – The Transcendent Story ending

What does make us feel the rapture of being alive? What will deliver that?

Let’s forget about story for a minute and think about what it is in real life that gives us that feeling. I would say, ironically, that it’s a funeral.

In real life, I’d say it’s often the funeral of someone very close that will, ironically, make you feel the rapture of being alive.

The common perception of funerals is that they are sad affairs and, in certain tragic circumstances, I can imagine it would be difficult to find any redeeming dimension.

However, at the funerals of the people to whom I have been closest – my father, my best friend and another good friend who committed suicide – I left those ceremonies absolutely feeling the rapture of being alive. Why?

Because, while I felt the heart-wrenching pain of knowing that I would never enjoy their company again, I was reminded, by the anecdotes I heard, of the qualities that made me love them – of their generosity, their courage and their humour, but of their quirks and weaknesses too. I felt blessed to have known and been loved by someone who was an extraordinary human being. And, possibly most importantly, I was reminded how fortunate I was to be alive and left the graveside determined to make more of the time I had remaining.

In feeling the grief of their loss, but also the joy of their memory and the inspiration to live life a little better, there is no question that I had a transcendent experience. It wasn’t an occasion that I could characterise as either happy or sad. It was Ecstatic Agony.

What other art forms, besides film for the moment, give us this exquisite, yet contradictory feeling that I’m talking about?

”I dreamed a dream” – soaring grief

The most moving part of the musical, Les Miserables, is when Fantine sings “I dreamed a dream”.

Now, this is not a feel-good story. She’s been jilted, left with child and had to resort to turning tricks in Parisian alleys. She sings, “I had a dream that my life would be so different from this hell that I’m living”. So, based on the lyrics, we should be feeling sad, shouldn’t we? Is that what we feel? No, it’s not.

Why not? Because the music is soaring. The words take us down, but the music takes us up and the tension between the two is profoundly moving. I don’t cry. I sob.

Opera does the same thing to me. In the great arias, the soprano is typically not feeling tickety-boo about life, but you wouldn’t know it from the music.

In Tosca’s famous “Vissi d’Arte”, the eponymous character is contemplating having to sleep with the malevolent Scarpia to save the life of her lover Cavaradossi and questioning why the God she has only honoured would deal her this fate.

In La Boheme’s “Donde lieta usci”, Mimi sings about terminating the relationship with the love of her life, Rodolfo.

In Madama Butterfly’s “Un bel di”, Cio-Cio San’s heart is aching because she has waited for years for the sight of a ship carrying BJ Pinkerton, the father of her child, to enter the bay.

The words in all of these famous pieces of music tell us that the characters are grieving but the music carries us up into the stratosphere and the pull of this emotional rack has touched audiences for more than a century.

That’s the power of Ecstatic Agony.

Before we return to film references, let’s consider another art form: poetry.

Ode on Melancholy – Keats gets Ecstatic Agony

When I was studying in LA, I had the great fortune to be taught by UCLA English professor, Lynn Batten, who not only introduced me to Campbell’s The Power of Myth but who also directed me to Keat’s Ode on Melancholy. Bizarrely my first experience of the poem was reading it standing up in the aisles of the Beverly Hills Public Library but it resonated with me immediately.

Here is an extract:

She dwells with Beauty—Beauty that must die;

And Joy, whose hand is ever at his lips

Bidding adieu; and aching Pleasure nigh,

Turning to poison while the bee-mouth sips:

Ay, in the very temple of Delight 25

Veil’d Melancholy has her sovran shrine,

Though seen of none save him whose strenuous tongue

Can burst Joy’s grape against his palate fine;

His soul shall taste the sadness of her might,

And be among her cloudy trophies hung. 30

This poem speaks to me of the gloriously painful duality of life – “Ay, in the very temple of Delight, Veil’d Melancholy has her sovran shrine”.

It also says that, if we are feeling grief, it is only because we have experienced the very best that life has to offer – “Though seen of none save him whose strenuous tongue can burst Joy’s grape against his palate fine”.

This articulates powerfully the complicated range of feelings we feel at a funeral. We are only able to feel great pain if we’ve been fortunate enough to know great love.

I believe that it’s only through experiencing these extreme and disparate emotions that we as human beings will be profoundly moved.

But how does this apply to film?

Ecstatic Agony in the great movie endings

If you want your film to profoundly move us and to make us, as Joseph Campbell exhorted, “feel the rapture of being alive”, I believe that your ending can be neither simply happy nor sad, but that it should conjure these contradictory sensations that I call Ecstatic Agony.

Let’s consider the great movie endings, and see whether it applies.

SPOILER ALERTS

In Dead Poets Society, Todd takes a lone, courageous stand to honour his wrongly maligned teacher, Mr Keating, but this high is tempered because it falls within the long shadow created by the suicide of his best friend, Neil.

In The Godfather, Michael triumphs over the other mob families by simultaneously massacring their leaders and this has to it a degree of primal triumph, but in the process he has compromised his morals, a fact which is brought home to us when the door closes so symbolically on the relationship with his wife, Kay.

In One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, the Chief escapes the institution and returns to life but only after the loss of Billy and R.P. McMurphy.

I could go on. The Lives of Others. Thelma and Louise. ET. Casablanca. Schindler’s List. To Kill a Mockingbird. All the films that are broadly considered to be Transcendent Stories, have endings that touch both ends of the emotional spectrum, they’re all profoundly moving and they’ve all succeeded both commercially and critically.

While a happy ending or a sad ending might play to some audiences, and an ambiguous ending will appeal to a niche who want to think rather than feel their way through a film, if you want to write a Transcendent Story that cuts across these divisions and really helps us with being human, then I would encourage you to consider an ending that embraces the duality of Ecstatic Agony.

In my next post, I’ll give you some tips on how to craft a story that can produce this complex and emotionally potent ending.

When is my next 2-day screenwriting course?

Please add me to the Cracking Yarns mailing list

Other posts you might like to read:

Radical Solution to the Hollywood-Indie standoff – Character and Story in the same screenplay

How to win audiences and Oscars – introducing the Transcendent Story

Transcendent Story Pt 2: 5 qualities that elevate the great films above the good