In my last post, I explored the Ecstasy that tends to balance the Agony in a great movie ending. Here I look at what the Hero needs to do in order to elevate our feelings to that transcendent place.

Most people set out to write an emotionally engaging movie. They want to move us. And when you look at the climax of the film, you get the sense that they are really willing us to feel something. But, most often, we won’t. Because wanting the audience to feel something, and having them feel it, are two entirely different things. And the thing that will most often tend to undermine the emotional power of a climax is that the resolution comes too easily. The writer doesn’t make it hard enough for the hero. And making it harder doesn’t necessarily involve making the antagonist six inches taller or forty IQ points smarter.

There is hard. And there is devilishly difficult

Difficulty comes in varying degrees. David facing Goliath is difficult. He’s facing an antagonist stronger than he is. Just as Brody does in Jaws. But, a higher degree of difficulty comes when there is a choice involved. What choice does Brody have as that Great White bears down on him? Yes, he exhibits smarts in the way that he overcomes the shark. But there really is no choice that demonstrates character (where “character” here means “exhibits the higher attributes of humanity”). It’s tough and it will deliver a very fine Cathartic film. But, for a Transcendent Story, it needs to be tougher.

At the risk of antagonising the Raiders fan club again, I will point out that Indiana too doesn’t really face a choice at the climax. Not only are the two things he wants – the Ark and Marion – in the same place, but he isn’t actually active at the climax. You could say he makes a choice not to watch, but that doesn’t involve character. That is intelligence or knowledge which has nothing to do with character – there are a lot of smart, knowledgeable people who are complete arseholes. This is another reason why this wonderful film – for all its virtues – does not move us to tears. That’s what we’re exploring here. The profoundly moving.

And if you want your film to be profoundly moving, I would suggest you present your hero with a devilishly difficult choice at the climax – a decision that demands an expression of character.

In Dead Poets Society, Todd can allow the teacher he reveres to leave the school a scapegoat and feeling that the students have been unaffected by “Carpe Diem”, or literally take a stand and incur the wrath of both the school and his family. He doesn’t have to do anything. He must choose to call on his Higher Self.

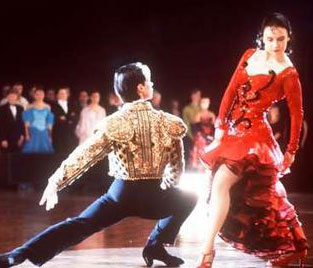

In Strictly Ballroom, Scott’s dream is within his grasp. All he has to do is dance the Federation steps and the Pan Pacific championship is his. But, that would mean not honouring what he feels inside. The title he’s always desired or forego that to dance to his own rhythm? He must make a choice.

In Schindler’s List, Oscar can take the suitcases of money he’s accumulated and spend it on wine, women and Mercedes limousines, or use it to spare the lives of the workers he’s come to love. He doesn’t have to save them. It’s a choice that involves giving up everything that has defined him.

In Kramer vs Kramer, Ted can appeal the decision that gives custody of Billy to his ex-wife. But that would mean putting Billy on the stand. Whose interests will he put first? His own or his son’s? He must choose.

In The Lives Of Others, Wiesler can allow the Stasi to arrest the playwright and his girlfriend for whom he has come to care, or he can step in to spare them and risk his safe position inside the party. The easy thing, the pragmatic thing, would be to let them suffer their fate. They will only have a chance if he chooses to act.

Why do we like our heroes to face dilemmas?

I think we like our heroes facing tough choices because we know that life rarely presents simple options. We almost always must make a choice between alternatives with competing virtues. Very often there is what we would like to do for ourselves vs what we feel we must do for the people we love. The selfish choice vs the selfless choice. The preference of the child over the obligation of the adult. We will be tempted to take the former but we know that our Higher Self will gnaw away at us unless we take the latter.

Which option will the hero take? That leads me to …

Great Endings Step 4: Do in Act 3 what they couldn’t do in Act 1

Earlier posts in the How to craft a Great Ending series:

10 Steps a Great Movie Ending

Great Endings Step 1: Hero shouldn’t get what they wanted

Great Endings Step 2: Hero should get something move valuable

Join the Cracking Yarns mailing list

Learn about our Screenwriting Courses

Learn about our Online Screenwriting Courses

Learn about our Free Screenwriting Webinars

Learn about our Script Assessment options

Subscribe to the Cracking Yarns YouTube channel